Sunday Morning Coffee — September 25, 2022 — A Hall of Famer Without The Plaque

This was supposed to be a Sunday Morning Coffee bye week. Then Mike Labanowski called on Tuesday morning.

“Just wanted you to know, and it’s not public yet, that Maury died last night,” Labs, my longtime baseball playing and recent African safari mate emotionally told me.

Maury is Maury Wills. If you didn’t follow baseball through the 1960s, or are too young, the name probably means nothing to you. Those were the days when baseball, horse racing and boxing dominated the sports landscape. Football and basketball were niche side shows. The days when people actually read daily newspapers, watched Lawrence Welk, collected dimes for pay phones and listened to transistor radios.

If you were a baseball fan from back in the day, you know that with two legs, Maury Wills changed the sport. He was a base stealer and an offensive weapon like the game had never seen before. In 1962 he stole 104 bases slashing Ty Cobb’s previous record of 96 that stood for 47 years or to when Woodrow Wilson was getting home delivery of the Washington Post at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

At one time I hated Maury Wills. He led the Dodgers to World Series championships in 1959, 1963 and 1965 leaving my beloved Pittsburgh Pirates in the dust. Then in 1967, with his legs battered and beaten, he was traded to the Pirates for Gene Michael and Bob Bailey. I then loved Maury Wills even though he could never help deliver the title to Pittsburgh the way he did three times in LA.

I got to know Maury many years later. Labs befriended him at Dodgers fantasy camp in 2006. They built a close, personal relationship until Wills’ death last week at the age of 89, less than two weeks shy of his 90th birthday.

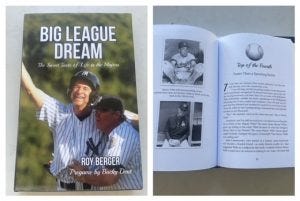

After I wrote my first book, The Most Wonderful Week of the Year in early 2014, I said I would never write again. I stayed true to my word. For about two years. Then at a Yankees camp in November 2014 I got a game winning walk-off hit against an undefeated, unbeatable team. That in itself was memorable but then Cliff Welch, the camp photographer, screwed things up by capturing the celebration image perfectly. Somebody then commented, “Well, it looks like you have the cover picture for your next book.” I immediately groused back, “I’m not writing another book.” Yada, yada. Big League Dream (www.bigleaguedream.com) was published eighteen months later. Instead of a story about me trying to play baseball in a major league uniform at age 57, which was the focus of The Most Wonderful Week of the Year, I wrote about the baseball gods that we worshipped as kids. Decades later I’m playing ball with them at various camps. They were in the dugout managing us, laughing, as we try to emulate what we idolized as kids. Time had become an equalizer and now we were all equally over the hill. Personal relationships developed; we were now in common phases and stations of life with our former heroes.

Wills was a classic chapter for my 2017 Big League Dream.

So, for the book I wasn’t writing I began to put together a roster of players whom either I knew or had access to through others. I wanted to profile guys who had interesting backgrounds both as kids and major leaguers. I wanted to tell their story, and how years later we literally landed on the same playing fields together. Bucky Dent, Jim ‘Mudcat’ Grant, Fritz Peterson, Steve ‘Psycho’ Lyons, Jake Gibbs, Gary Bell, Ron Swoboda, Mike LaValliere, John Mayberry, Chris Chambliss, Jon Warden, Dennis Leonard and Kent Tekulve all gave me their time to be profiled in Big League Dream. Old time baseball lifers remember most of those names.

Labs asked if I would like to include Maury Wills. “Maury Wills?”, I shouted back. “You do know I hated Maury Wills as a Dodger but would I love to tell his story. But come on, don’t be teasing me.”

Wills was beyond terrific. Maybe my favorite interview among the fourteen I conducted. (Only kidding Bucky Dent and Mike LaValliere who read SMC; he was second only to you guys). Maury’s memory, even in his mid-80’s, was tremendous. He loved to laugh and spoke for hours until my tape ran out. We did it all over the phone. He on the back porch of his home in Sedona, Arizona, with wife Carla at his side. I named his chapter, ‘Faster Than A Speeding Bullet.’ Pretty clever, eh?

Like most of the old-time ball players, Maury loved to tell stories. He spent eight years in the minor leagues before hitting the show in 1959. It was tough to get a big league job in the Dodgers organization with Pee Wee Reese ingrained at shortstop. He painfully recalled being the only African American player in bush league towns when he couldn’t use the same rest rooms, drinking fountains, restaurants or hotels as his white teammates. Most of them boycotted those places if Maury couldn’t be with them. He laughs when remembering a game in ‘62 when Mets pitcher Roger Craig threw to first base 12 straight times trying to pick off him off. The 13th toss was finally to the plate and Maury promptly stole second. That same year the All-Star Game was in his home city of Washington D.C. Wills spent the night before the July 10, 1962, game at his family’s home instead of the downtown hotel with the rest of the National League All-Stars. He was only 5’11”, weighed 170 pounds soaking wet and a very youthful looking 29 years old. He showed up at D.C. Stadium and the security guard refused to let him in the players entrance, not believing he was one of the All-Stars despite carrying a Dodgers duffel and wearing a LA cap. He finally convinced the guard to escort him to the National League clubhouse door where the players would vouch for him. The security guard opens the door and asked a couple of the players near-by, if “Anybody in here know this kid?” In on the joke, they responded, “Never saw him before.” Eventually everybody got a good laugh including Maury and the embarrassed security guy. Wills didn’t start the game but entered in the fifth inning at shortstop for Dick Groat. Maury was one for one at the plate, a stolen base and two runs scored in the NL’s 3-1 win. He was selected the game’s MVP and on the way out delighted showing the disbelieving security guard his trophy.

That same season he was also voted the National League’s MVP even though the Giants’ Willie Mays hit 59 home runs and took San Francisco to the World Series after beating the Dodgers in a three game playoff. Wills, a switch hitter, batted .299 in 1962, led the NL in singles and triples, scored 130 runs, won the Gold Glove at shortstop and of course, swiped 104 bases in 117 attempts for an 89% success rate. Not even Al Capone was that good.

The master thief with his 1962 haul of 104 stolen bases.

The missing link in Wills’ career was never being enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame, despite an organized effort from his legions of fans until the day he died. He had the numbers: in a 14-year career hitting .281, with over 2,000 hits and 586 stolen bases. He was a seven time All-Star, two time Gold Glove winner, three time World Champion, an MVP and six times he led the NL in stolen bases. However, none of that was good enough for a bust and plaque in Cooperstown. Ironically, his rival in the American League, shortstop Luis Aparicio had a lifetime batting average of .262, twenty points lower than Maury, and despite playing four years longer stole eight less career bases. Aparicio was inducted into the Hall in 1984.

Who knows why? Maury’s stint managing the Seattle Mariners for two seasons in the 70s was a disaster. Following there was a real rocky period in his life with alcohol and cocaine dependency which perhap alienated many HOF decision makers. His finances, reputation and relationships suffered. He had been clean since 1989 turning into a gracious, respectful, kind and appreciative gentlemen living out the final innings of life.

Wills told me, “I stopped worrying about the Hall of Fame a long time ago. If the call is supposed to happen, it will.” It never did.

Humbly Maury also said, “I know I changed the game in many respects, but I don’t think I ever arrived at what my potential could have been.” Scary words for every catcher who tried to mow him down on the bases.

With as much time as we spent speaking, I have one distinct Wills memory. It was a chilly, early winter night in Birmingham, Alabama, in 2016. I was going to a basketball game and just as I parked my car the phone rang. It was from a SoCal area code but a phone number I didn’t recognize. However, it was a good day for me already: I got a call telling me I had won a cruise to the Bahamas; all I had to do to claim it was give them my credit card number. A little later a gentlemen in the Philippines told me I had a really bad computer virus but if I had my MasterCard handy he could fix it, even from so far away. So with my luck running strong, I answered the unknown phone call.

“Roy,” the squeaky voice on the other end said, “this is Maury Wills.”

As a 10-year-old kid hating him or a 64-year-old respecting him, it’s still words I never expected to hear. A couple of days earlier I had sent him a proof of his chapter in Big League Dream.

Wills said: “I just want you to know I think you are a hell of a writer.”

I was flustered. Surprised that he actually called me and then verklempt about what he said.

All I could think to say in response was a not very polished, “Maury, I think you were a hell of a shortstop.”

What I wish I would have said was, “Maury, you don’t need a plaque to say what every baseball fan knows. You are a true Hall of Famer.”

You’ll always have the steal sign in heaven my friend. Run wild just like you did down here.