Sunday Morning Coffee — July 28, 2019 — Stealing First? Say It Ain’t So!

Move over Rickey Henderson, Lou Brock and Vince Coleman. You too Tim Raines, Maury Wills and Ty Cobb.

The now legendary Tony Thomas.

Open the door for Tony Thomas. You remember Thomas, don’t you? Drafted a dozen years ago in the third round by the Cubs and after a cup of coffee in AAA and lunch in AA, he’s now hanging on to the fumes of a career that never was. He’s playing out the schedule in the Atlantic League wearing the uniform of the Southern Maryland Blue Crabs and hitting a paltry .229. Try finding that jersey in Modell’s. He’s probably a month or so away from putting his Florida State University degree to use on a resume and look for a day job.

However, the thirty-three year old Thomas did something two weeks ago that Henderson and all the other hotshot great base stealers of yesterday never did. He became the first professional baseball player to ever steal first base!

Thomas was given the opportunity to become an obscure trivia answer when the Atlantic League, at the behest of Major League Baseball, agreed to try a new rule that allows any hitter to, at his own risk, attempt to steal first on any pitch “not caught in flight” by the catcher. In other words at your discretion you can be off to the races on a wild pitch or passed ball or even something in the dirt the catcher can’t find.

If you are scoring at home and the batter makes it successfully to first, as Thomas did on a 1-0 pitch that got past the Lancaster Barnstormers catcher, it goes down on the scorecard as a fielder’s choice but you get the base safely. If you are tossed out, it’s a conventional putout. Thomas made it without a throw as the pitch rolled all the way back to the screen.

MLB has adopted the independent Atlantic League as its socially-challenged nephew. It feeds its experiments into the lowly minor loop and monitors the results. Also this season the Atlantic League is using robo-umps to call balls and strikes; banning infield shifts; pitchers having to face three batter minimums and allowing one foul bunt attempt on two strikes before the batter is rung out. By and large the League is a lot like Capitol Hill— it’s where ideas go to die. “It’s also where players go to die,” quipped former Yankee Jim Leyritz.

MLB is trying to create more offense and excitement, something that might appeal to a younger demo that finds the grand game stale and boring. Originally I thought the stealing first idea was ridiculous. But the more I thought about it mornings on the treadmill, the more I became intrigued by the importance of every pitch and the more I grew to like it.

The one thing I had no doubt about was who wouldn’t like it— the ballplayers. Especially the older ones that we worshipped as kids. So I went to my fantasy camp rolodex and got a hold of some of the guys I’ve befriended over the past decade when I’ve put the uniform back on trying to be something I never was.

If you are looking for bi-partisan support among ballplayers, just go ahead and try to change the rules of the game. Dems, Republicans, American or National League, it doesn’t matter. There’s unanimous across-the-aisle-support that the game was fine the way it was ‘back in the day.’ Just leave it alone.

Pitchers, catchers and even hitters are pretty much in agreement stealing first should never advance beyond where it is now— experimental and doomed to fail.

No position faces more pressure to keep an eye on the basepaths than catchers. They don’t need another headache of worrying about a batter being able to run on them, too. No position in baseball is tougher than being a catcher. None that play the game are tougher than catchers.

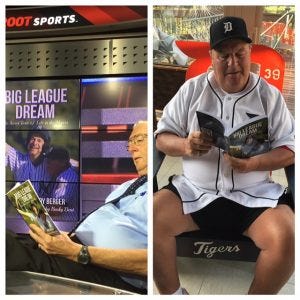

A couple of ex-catchers who predictably hate the proposed stealing first rule. LaValliere (l) sharpens up on his quality reading while I bumped into Leyritz at the 2018 BCS championship game. Roll Tide!

Leyritz and Mike LaValliere are a couple of tough guys. They also are ex-catchers. Leyritz played eleven seasons from 1990-2000 with over 900 games in the bigs. He caught about a third of them with the Yankees, Angels, Red Sox, Padres and Dodgers. He has two World Series rings as a Yankee, 1996 and 1999, and will always be remembered for his key ‘96 World Series home run in Atlanta that helped the Yankees erase a 6-0 deficit in Game 4 to come back and tie the Series at two games apiece en route to a six game win over the Braves. He was also part of San Diego’s 1998 National League championship team.

LaValliere, a dozen years in the game from 1984-95, was known as a defensive stalwart behind the plate during his career with the Phillies, Cardinals, White Sox and Pirates.

Not surprisingly, they both hate the idea of stealing first.

“I think it’s ridiculous,” the fifty-eight year old LaValliere said. “It increases the pressure on the catcher tenfold. There are two general stances when you are catching— the relaxed, comfortable, nobody on base position that would be eliminated. For every pitch, you would have to be in the active, block the ball at all times stance. It becomes a huge advantage to the hitters and for a guy that can run, it’s incredible. If this ever happens they better figure out a formula to compensate catchers for the number of pitches they block.”

Leyritz, fifty-five, also doesn’t mince words. “I think it’s a complete joke. That’s not baseball. Baseball is four balls and three strikes. Earn your way on base. Doing something like this changes the strategy of the game,” the Kentucky alum, who’s reinventing himself as a realtor for Keller Williams on Long Island and in New York City said. He added, “as a catcher I can’t have my pitcher waste an 0-2 pitch anymore. Everyone knows the 0-2 pitch sets up the next one and with this rule you run the risk of giving a guy a free base. I don’t like it at all.”

Pitchers obviously would be the most impacted. There’s nothing positive that can happen for a pitcher if the batter has a chance to run on every pitch.

Kent Tekulve pitched out of the bullpen for sixteen seasons from 1974-1989. He spent thirteen of those years with the Pirates followed by brief stints in Philadelphia and Cincinnati. He appeared in 1,050 games earning the moniker of “Rubberband Man” for his resilient right arm that never seemed to tire. He still holds the National League record for career innings pitched in relief (1436) and he saved three games in the 1979 World Series as Pittsburgh beat Baltimore. Teke retired with a career ERA of 2.85 and 184 saves.

“I’m against all these rule changes baseball is doing,” the 1980 All-Star said. “I think the game is just fine. A lot of this stuff is changing the game just for the sake of changing it and I think that’s what’s happening with the stealing first experiment. There is no logical reason to do it.”

Tekulve, now seventy-two, was a submarine-style sinkerball specialist noted for his great control. Because of that he doesn’t think the ability of the batter to steal would have greatly affected him. “But it certainly would become an issue for non-control pitchers,” the gentlemanly 2014 heart transplant recipient said. “I was a sinkerball pitcher that was blessed with a great group of catchers so it wouldn’t impact how I pitched a game.

“Except for one hitter,” Teke laughed. “Willie McGee was not only fast but I tried to get him to chase alll sorts of stuff outside the strike zone. I would have been a lot more cautious with what I threw someone like him if he had the ability to steal first,” he admitted and added, “just leave the game alone please.”

Jon Warden was the anti-Tekulve. He pitched one year in the bigs, 1968, and made it count before a torn rotator cuff ended his career. Rubberband Man he wasn’t.

Like LaValliere, Tekulve (l) and Warden know a great book when they read one.

Warden’s Detroit Tigers won the World Series in ‘68. He was a left handed relief pitcher that went 4-1 that season with a 3.62 ERA. He is the only relief pitcher in MLB history to win his first three appearances. However, he also was the only player on the Tigers and St. Louis Cardinals World Series roster that didn’t get into a Series game, though he joked “they let me warm-up once in the bullpen.”

Warden, also seventy-two, parlayed that one World Championship ring into a career as a humorist, motivational speaker and stand-up comedian who’s opened shows for Jeff Foxworthy and Larry the Cable Guy and was co-host of ESPN’s Cold Pizza. He too hates the stealing first idea.

“This kind of stuff drives me crazy. It’s the dumbest thing I ever heard of. That’s baseball? Really? I don’t think so,” Warden said. “In 1966, my first year in the minors at Daytona Beach, our manager Gail Henley fined any pitcher that gave up a base hit on an 0-2 count five dollars. When you are making $100 a week that is a pretty big dent. So guys used to throw an 0-2 pitch back onto the screen or into the dugout or to the plate on four bounces. Anything they could do to make sure the batter couldn’t hit it. If we played back then with this ridiculous stealing first rule it could have cost us five bucks and a base runner!”

Homer Bush and Jose Lind are a pair of former big leaguers that could have benefitted from the ability to steal first. Bush played eight years in the majors with the Yankees, Blue Jays and Marlins as an infielder. He was a World Champion in 1998 with the Yankees hitting .380 in forty-five games. He retired in 2004 because of a hip injury with a .285 career average.

Lind, fifty-five, was a sure-handed second baseman with nine years in the bigs, most of them in Pittsburgh, while finishing his career with the Royals and Angels in 1995. He was a career .254 hitter and spent three seasons managing Bridgeport in the same Atlantic League fifteen years ago.

Bush (l) is incredulous on how slow one old guy can be. Lind shows us he can still make the pivot at second.

Bush and Lind were also among the best base stealers in the business with an identical 76% success rate, so this experimental rule would have been right up their alley. Or so you would think.

“I think the rule is a bit extreme but as a hitter I like it,” Bush, whose smile can light up Miam Beach at high noon with an infectious laugh to compliment his outgoing personality. “Being able to run at any time will force pitchers to be around the plate more often and for hitters that’s a good thing.”

However, Lind isn’t a supporter. “They are trying to change the game and I don’t like it at all. What I think needs to change is the attitude of the players today. We’ve lost respect for the game. Guys don’t run out ground balls, they don’t hustle. Most of them seem to only care about themselves and their contracts. If they are going to be charged with an official at-bat by trying to steal first, I wouldn’t be surprised to see some guys just stand there and wait for a pitch they can hit. We can do better as a game than we are doing today and that’s what needs to change the most.”

Bush, forty-six, sees how the rule can be used to his advantage. “The later we got in a game the main priority for me was finding a way to get on base,” he said. “If this is the way I have to do it, charged at-bat or not, I’ll take it. I had to figure if I can get to first, I can steal second and be in scoring position,” he added, “but it will never will happen in the big leagues. There’s no chance. The pitchers won’t let it!”

The likeable Leyritz summed up stealing first base in true baseball terms.

“I think the idea should be treated like a scruffed up, old ball,” he chuckled. “Just toss it out of play.”

No worries, Mr. Leyritz. There’s a better chance of Nancy and Paul Pelosi, Iris and Chuck Schumer and Ann and Robert Mueller rolling up to 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. in their formals for the ‘No Obstruction/No Collusion Gala’ under the stars on the White House East Lawn than anyone being able to steal first base anytime soon at Yankee Stadium.

And for baseball purists, that’s a good thing.