Sunday Morning Coffee — December 5, 2021 — Crossing Paths with a Baseball Lifer

Bill Virdon was different from us kids growing up in the 50s and 60s. We loved baseball and watched from the bleachers or on television or enjoyed the passion of our favorite hometown broadcaster on radio describing the games’ every nuance. While we viewed and listened from afar, Virdon spent his life between the white lines. He was a true baseball lifer.

The small mention in agate type in your daily sports section on November 23 memorializing Virdon’s passing at age 90 meant nothing to most everyone save for the few, true baseball fans still around from back in the day. I’m one.

From my earliest baseball memory until the day he died, Mr. Virdon was part of my childhood and unpredictably later, my adult life.

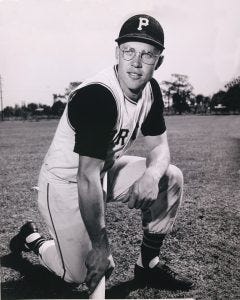

Virdon in his playing days.

On the ball field, the Springfield, Missouri, gentleman did it all. He was a smooth and graceful center fielder for the Cardinals, named the National League Rookie of the Year in 1955 at age 24 before being dealt to the Pirates two years later. He won a Gold Glove in 1962 for his defensive prowess; was a two-time World Champion with Pittsburgh and after his playing days were over he moved into the manager’s seat serving the Pirates, Yankees, Astros and Expos.

Even though I was only eight, I was a Pirates fan in 1960. I knew who Bill Virdon was before October 13, 1960, when the Pirates played the Yankees in Game 7 of the World Series. My dad said I knew my baseball better than my third grade arithmetic. Was that wrong? I was a Pirates fan because my dad was. I thought that was the way it was supposed to be. Living on Long Island, we were probably the only two.

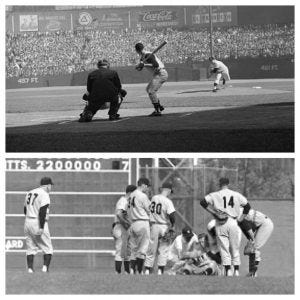

I wasn’t home from Meadowbrook Elementary School yet when Game 7 went to the bottom of the eighth inning: the hated Yankees were up by three runs and only six outs away from another World Championship. The Pirates were huge underdogs in the Series and now even longer odds, down three with two innings to go. Pinch-hitter Gino Cimoli singled to lead off the Pittsburgh eighth. Virdon, batting in the leadoff spot in the lineup, was a left-handed batter stepping in to face New York southpaw Bobby Shantz, who was in the game in relief of Bob Turley and Bill Stafford.

I was on the school bus listening to the game on something we called a transistor radio. A compact little contraption you could put right next to your ear to hear the Coasters, Chubby Checker or even NBC radio’s Chuck Thompson doing World Series play-by-play. It was pretty cool. It wasn’t hard to picture Bill Virdon because he wore glasses when he played. Almost nobody else did. Thompson relayed to the listeners that Virdon swung late on a Shantz curveball and hit a grounder to Yankees smooth-fielding shortstop Tony Kubek. He portrayed it as a certain double play effectively taking the Pirates out of the inning. And then maybe the most famous rock in World Series history came into our ears: the ball on the way into Kubek’s glove hit a stone and ricocheted right into Kubek’s throat knocking him down like a right cross from then heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson. Kubek took an eight count and left the game, replaced by Joe DeMaestri, who no doubt was munching on cheese and sampling the imminent champagne that was forthcoming in the Yankees’ clubhouse. It was a game changing rock.

Top- Virdon batting against Whitey Ford in 1960 World Series Game 3.

Bottom- Kubek felled by a rock. Looking on are Casey Stengel (37), Clete Boyer (34), Bobby Shantz (30) and Moose Skowron (14).

The Pirates, instead of two outs and the bases empty, now had first and second, nobody out and the stage set for a five-run inning to erase the 7-4 Yankees lead and take a 9-7 advantage into the ninth. The Yankees, now all of a sudden facing elimination, came back and tied it with two runs in the top half of the inning, but that was nothing more than a prelude for Bill Mazeroski, who waited until I raced home from the bus stop, and on the second pitch from Ralph Terry hit a walk-off home run to win the World Series. The Pirates celebrated and so did I, running around my street waving my Pirates helmet just like Maz did. I then impatiently waited by our front door for Dad to get home so we could celebrate our championship together with a big hug like our heroes did on television. Thank you Bill Virdon for hitting that rock and creating a memory for me with my dad that has lasted a lifetime.

Virdon was known as Quail during his playing days, partly for his hunting skills but mainly for his penchant to hit soft fly balls that dropped between the infield and outfield for base hits. They reminded Pirates play-by-play voice Bob Prince of a dying quail, thus the tag stuck. Virdon finished his playing career in 1968 as a lifetime .267 hitter and a steady-eddie in center field. Perhaps most impressive he batted .404 against the Dodgers’ Sandy Koufax with 21 hits in 52 career at bats against the legend. As solid a ballplayer as Quail was, he was overshadowed in that era by fellow National League outfielders named Willie, Hank, Roberto, Duke and Stan the Man. Virdon stayed in baseball after his retirement and was a coach on the Pirates’ staff when they won the Series again in 1971. The next year he was appointed the Pittsburgh field manager, at 41, a lifelong ambition. He also managed the Yankees, Astros and Expos over a 13-year period winning more games than he lost with a 995-921 record.

It was 50 years after the 1960 ground ball that changed the World Series when Virdon came back into my life. This time not as part of a box score or on television screen; instead, we shared a dugout wearing Pirates uniforms. Pinch me please.

My first foray into baseball fantasy camp was in 2010. Something I always wanted to do and that year the Pirates celebrated the 50th anniversary of the 1960 World Championship team as the theme of Pittsburgh Pirates Fantasy Camp week in Bradenton, Florida. I went because Andi pushed me out the door to do it. I had no idea what to expect or if I could even play anymore. I was 57. I doubted I could. A dozen alumni from the 1960 Pirates were at the camp to be our on-field coaching staff and our night time drinking pals and story tellers. I wasn’t nervous; scared shitless was probably a better descriptor.

I stepped onto the playing field, for the first time since high school in 1968, with 70 other slugs with the same diminishing skill levels that I had. The Pirates from 1960 and some later day ex-pros were watching and scouting us during an ‘evaluation’ game. Afterwards the pro staff on hand would go into closed quarters and choose their teams for the week. I somehow got a couple of legitimate and unexpected base hits during the scrimmage, undoubtedly moving me from the risk of Mr. Irrelevant, picked last, to somewhere in the middle of the draft pack. I was the perfect first baseman: tall, left-handed and slow. Very slow.

The next morning I found out that I was selected to play on the team managed by Virdon with former big league pitcher and character Jerry Reuss as our coach. I met Mr. Reuss at dinner the night before. I hadn’t yet introduced myself to Mr. Virdon until we were ready to take the field for our first game. His firm, Midwestern handshake just about sent me back to the trainer’s room to see if my right hand was broken. Virdon put me in the lineup playing first base and batting sixth, both spots justifiable.

And that’s part of the attraction of major league fantasy camp. Playing baseball way past the time in life you should be doing it and getting to kibbutz with ex-big leaguers you idolized as a kid. Bill Virdon was as classy as his reputation.

I couldn’t resist asking him about the ground ball he hit in Game 7, specifically what he was thinking when he saw it was right to Kubek. “Oh shit,” was his unrehearsed quip.

Virdon saw that gleam in my eye. All week. One morning midway through camp we were getting ready to play and sensing that youthful excitement I had, he strolled over to me and, in words I never thought I’d hear from a major league manager, asked, “Berger, do you want me to put you in the lineup today or take a rest?” Put me in coach, I’m ready to play. Okay, I didn’t really say that. Instead, I gave him a look that said if I wanted to sit, I would have stayed home in Alabama.

The other conversation I couldn’t wait to have with him was about his two years managing the Yankees. Well, not quite two years. Quail was hired in 1974 as a replacement for Ralph Houk but Virdon wasn’t Yankees’ owner George Steinbrenner’s first choice for the job. That belonged to Oakland’s Dick Williams. It fell apart when the Yankees and A’s couldn’t agree on compensation to Oakland, who still had Williams under contract. Virdon had been let go by the Pirates the previous winter, and it was no secret he was a Yankees fill-in until somebody more to Steinbrenner’s liking came along. Virdon upset the plan by doing too well in his first season. He led the Yankees to a second place finish in the AL East, one game behind the powerhouse Baltimore Orioles. For that, Virdon was selected American League Manager of the Year by The Sporting News. Steinbrenner had no choice but to bring him back the next season.

Virdon managed the Pirates, Yankees, Astros, Expos and me.

The Yankees stumbled in 1975. Virdon also came under pressure by the New York media, the Yankees’ fans and some of the players for using Elliott Maddox as the regular center fielder instead of popular Bobby Murcer. A death threat even found Quail’s mailbox. Steinbrenner, suspended from baseball that season for making illegal campaign contributions to President Richard Nixon’s reelection campaign, was supposed to have nothing to do with the operation of the team. But he didn’t think that stopped him from telling Yankees president Gabe Paul what to do. Paul was Steinbrenner’s Mike Pence. The order on August 2 was to fire Virdon when Billy Martin became available. The rest is Miller Lite lore.

Virdon is the only Yankee manager to never manage a game in Yankee Stadium. During his season and a half in 1974-75, the Stadium was under renovation and the Yankees played their home games in Queens at the Mets’ Shea Stadium.

Chatting about his time in Pinstripes and probing a little bit, he was much too much of a gentleman to throw darts. “I enjoyed the experience, let’s leave it at that,” was the best I could get. I hate when that happens.

Houston hired Virdon three weeks after the Yankees fired him; he spent eight successful years in the Astrodome, which included being selected National League Manager of the Year in 1980 when the Astros won the NL West.

Quail and his stud first baseman.

He finished his managerial career in Montreal where, after two seasons, he chose not to return for a third in 1985. For the next 15 years, Quail served on the coaching staffs in Pittsburgh, St. Louis and Houston before calling it a career in 2002. He couldn’t stay away totally, and for 15 more years was a special spring training instructor for the Pirates marking 65 years in the game. Only Shirley, his wife of 70 years, was more of a love than baseball.

Health concerns slowed him the past few years. His last year at Pirates fantasy camp was 2015 and his passing the week before last was sadly no surprise.

As our 2010 camp ended with Virdon leading us to the camp championship game, I sought him out before I headed home to Birmingham to thank him for making the week so special. Virdon being Virdon, would have none of it.

Humble as billed, he looked me right in the eyes with his trademark lenses and said, “Roy, I guarantee I had more fun this week than you did.”

I don’t think so, sir. I don’t think so.