Sunday Morning Coffee — December 20, 2020 — The Music Man

Phil Linz died on December 9.

Was that a collective “Who?” I just heard?

Phil Linz was a marginal professional baseball player and a worse musician. Only a fellow old-timer, a hard-core baseball fan from the 1960s, would recall his name. A music aficionado from the same era never heard of him. There’s little doubt about that.

Linz won’t be remembered for his ability to hit a fastball or a high note. He will be remembered for an incident that combined the two.

In a way Linz, unbeknownst to us at the time, was a key cog in changing the landscape of sports culture and sports reporting from what it was then to the no-holds-barred approach of today. And it all started innocently enough with a new harmonica.

Phil Linz

Back in the day, the glory days of baseball through the 40’s, 50’s and right into the 60’s, baseball and the media covering the game had an unwritten pact. The media, mainly newspaper guys, restricted their coverage to what went on between the white lines on the field. Activities off the field were protected. The media kept their notebooks shut and in return the players accommodated them with access about the game. They traveled together, they ate together, they played cards together, they drank together, and they closed their eyes and shut their mouths together.

However, all of that changed late in the afternoon of August 20, 1964. Four days earlier the New York Yankees went into Chicago in a tight pennant race tied for first place with the White Sox. Four days and games later, the Yankees were swept and now were four behind.

Linz, 25, was a bespectacled utility infielder for the Yankees. He could play third, short or second base.

During that road trip, while killing time before a night game and strolling the downtown streets of Chicago, Linz stopped into a Marshall Field’s department store and walked out the proud owner of a harmonica, an instrument he had no idea how to play. Teammates and fellow infielders Bobby Richardson and Tony Kubek each bought one earlier in the road trip and Linz was keen to make it a trio.

When the Yankees departed Chicago’s Comiskey Park, after getting the broom, on their way to a weekend series in Boston, the traffic to O’Hare was backed up for miles. A 45-minute trip took two hours. Linz, bored, took out his harmonica and very quietly, in the back of the bus, played Mary Had A Little Lamb, following the notes from the arrangement on the harmonica box.

That’s the part of the story everyone agrees upon. What happened next had many different versions over the years.

I was a 12-year-old naive kid on Long Island, and this was the first scandalous baseball story I read in my daily Long Island Press or weekly Sporting News. I never knew baseball players had lives off the field. Who knew they took bus rides, airplane flights or walked around cities they were visiting? To us innocent kids they played ball. That’s all they did. That’s all we cared about.

When Linz died at the age of 81, my memory of the event was re-awakened. I hadn’t thought about it for years, but I keenly remembered the impression it had on me at the time. Over the past week, just for curiosity, the more I went back and read about the incident, the more conflicting tales there were. Just to satisfy myself, I took a look at the 1964 Yankees roster to see if, 56 years later, there was anyone on that bus, whom maybe I got to know, to give me a first-hand account of what really happened. Most of the guys on that team are now tossing a ball up in the sky, but there were two names that are in my iPhone rolodex: catcher Jake Gibbs and left-handed pitcher Al Downing. Both gentlemen I know from my five Yankees fantasy camps.

I called Mr. Gibbs first. In ‘64 Jake was still being platooned between the Yankees and their top farm team in Richmond, Virginia. He wasn’t recalled to the Yankees until September, so he wasn’t with the team for Linz’s August recital. However, that didn’t stop Gibbs from reminiscing for 30 minutes about other things that happened that year, as he is so wont and engaged to do.

Al Downing

I don’t know Mr. Downing as well as Mr. Gibbs. Downing, 79, was my Yankees coach at camp in 2018. He is a walking encyclopedia of the game. Most of these guys from yesterday have an incredible recall for the most trivial details, but Al is different—he remembers details and parlays situations from those days into how they impact today’s game. Like Gibbs, all you need to do is have your phone charged and be ready to listen. For me, conversations with old-time baseball players and old-time baseball junkies are addictive. I’m the junkie.

Al picked up the phone on the third ring at his Valencia, California, home. When I told him what I wanted to talk about, he didn’t miss a beat, almost like he was ready for the call.

“Sure, I remember it,” Downing who was 23 and in his second full season with the Yankees in 1964, chuckled. “It was a day game in Chicago and very hot. The bus was hot as heck too and it seemed like it was taking us forever to get to the airport. Plus, nobody was in a very good mood after losing four straight.”

The multiple different accounts of what took place on the bus ride that I read succumb to Downing’s recall. It’s sharp. Too sharp to second guess.

“There was that long bench seat in the back of the bus and Linz was sitting on it with Mickey (Mantle), Whitey (Ford) and Joe (Pepitone). Directly in front of Phil were Jim Bouton and Tom Tresh,” Downing said. “I was about five seats in front of them.”

He continued: “Guys were down in the dumps and Linz told Mickey he just bought a harmonica in Chicago and showed it to Mickey. Mickey said to play something.

“Phil told him he only knew Mary Had A Little Lamb. Mickey said to play it,” Downing laughed. “You could tell Phil had no idea what he was doing. He played it very softly.”

Yogi Berra was in his first year managing the Yankees and sitting in the front seat. He was in no spirits for a concert. Yogi turned to his third base coach Frank Crosetti, seated across the aisle, and asked where that music was coming from? Crosetti said it sounded like the back. Yogi told him to tell them to quit the ruckus. “Hey,” Crosetti yelled according to Downing. “Knock it off back there.”

The music continued and now Yogi was steamed. He got up and allegedly shouted “Cut it out and shove that thing up your ass.”

Linz didn’t hear him. He turned to Mantle, who was a team elder at 33, and asked ‘What did he say?’ Mantle, ever the practical joker responded, ‘He said to play it louder.’

“Here comes Yogi down the bus aisle,” Downing, who led the American League in strikeouts that season with a record of 13-8, remembered. “He was mad. Linz, thinking Yogi wanted him to keep playing, was looking down at the notes on the box and never saw Berra. Yogi goes over and swats the harmonica away from Phil and it falls right on Pepitone’s knee. Joe gets up and starts hoping around like he’s really hurt. Everybody got a good laugh out of it.”

Downing, who was a part of the Yankees starting rotation that season with Ford, Bouton, Ralph Terry and Mel Stottlemyre, added “To us the harmonica incident was never a big deal but there were media on the bus, and they built the story up to what it became.”

There were six writers on that bus. Allegedly, they all agreed not to report the story because it would look bad for the team. When they finally got to O’Hare, one writer reneged and called the story into his paper so the rest of them did too. By the time the Yankees got to Boston the incident was red hot news.

For me that was the beginning of the end of baseball sanctity. This kind of thing could really happen? Why weren’t the players as upset over the loss as Yankees fans were? Soon after, we read off-the-field stuff like Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale holding out for more money and refusing to report to the Dodgers in 1966. Three years later Curt Flood was traded from the Cardinals to the Phillies and legally challenged his right to say no. The game was changed forever by that decision which gave players the right to be free agents. In 1970 Jim Bouton shattered the privacy of the clubhouse by publishing his tell-all book, Ball Four. He was ostracized by his fellow players and baseball administration for that breach of trust. And in 1973 Yankees pitchers Fritz Peterson and Mike Kekich swapped wives and families in a tabloid stunner that even knocked Watergate off the front page of the Daily News and Post for a couple of days. Baseball left the field and headed for the courts and gossip pages, never again to be as pure as that 12-year-old kid believed it to be.

The 1964 fallout to harmonica-gate was extreme. Following the sweep in Chicago, the Yankees lost the first two in Boston. Linz was serenaded by harmonica playing from the Fenway Park crowd. But that was tame compared to four days later at Shea Stadium in the annual Mayor’s Trophy Game, an exhibition against the Mets. When Linz came to the plate for the Yankees, the Mets players good naturedly threw toy harmonicas at him. Back to Boston, the Yankees rallied to win the final two and then 28 of their last 43 games to beat the White Sox by a game for the American League pennant. It was their 15th pennant in 18 years. The Yankees lost the World Series in seven games to the Cardinals, ending their dynasty.

Yogi and Linz were in harmony two years later as Mets

Linz, a career .235 hitter, batted .250 in 1964. He was the Yankees regular shortstop in the World Series, filling in for an injured Tony Kubek and played every inning of the seven games. He batted leadoff and hit two of his eleven career home runs in the Series including a Game 7 blast off Bob Gibson. Downing pitched seven innings against St. Louis going 0-1. Following the Cardinals win, Berra was fired as the Yankees skipper. Though he was popular with his players, ownership cited the harmonica incident as part of the reason illustrating he couldn’t maintain control of his team and shipped Yogi out. The Cardinals manager, Johnny Keane, who just beat the Yankees in the Series was named Yogi’s replacement. The Yankees kept Linz around for another season before trading him in 1966 to the Phillies for Ruben Amaro. Midway through the ‘67 season the Phillies sent Linz to the Mets where, ironically, he was reunited with Yogi, a coach on manager Wes Westrum’s staff.

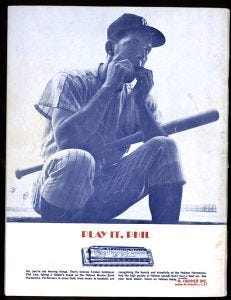

Yankees yearbook ad in 1965

Linz did get the last laugh, though. At least financially. He was fined $250 by the Yankees for the bus incident, a big bite out of a $14,000 salary. However, he was signed to a $10,000 endorsement deal by Hohner Harmonicas, which was also the instrument of choice for John Lennon and Bob Dylan. Yogi kidded Linz afterwards, “you should have cut me on that.” Everyone, except maybe Yogi, got a big kick out of the full-page advertisement on the back cover of the 1965 Yankee yearbook which featured Linz and his Hohner.

“If people remember me at all,” Linz told USA Today in 2013, “they remember me as a harmonica player, because I sure wasn’t too good of a baseball player.”

Right about now up in heaven the Almighty has finished his daily announcements. Linz, a heaven rookie, turns to 25-year resident Mantle and asks, “What did he say?”