Sunday Morning Coffee — August 3, 2025 (From August 5, 2018)— A Nice Guy Who Didn’t Want Anyone To Know It

By Roy Berger, Las Vegas, Nevada

(Note: This piece I wrote for SMC on August 5, 2018. Yesterday, Saturday, marked the 46th anniversary of the fatal airplane crash that killed New York Yankees star Thurman Munson on August 2, 1979. His life, and ultimately death, was personal to me. This past Wednesday night I was in Yankee Stadium and made sure to visit the Yankees Museum where Munson’s locker has been preserved. Even if you don’t remember Thurman, or not a baseball fan, I hope you enjoy this recollection. RB)

Some will ask, ‘Who was Thurman Munson?’ Others might recall the name. But if you are a baseball-loving boomer you either loved him or loathed him. Few were indifferent.

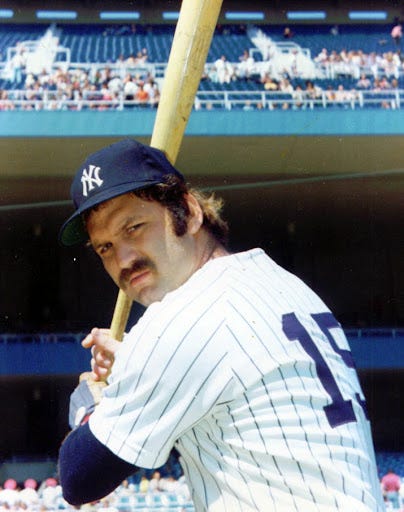

Thurman Munson was a catcher for the New York Yankees. He played baseball with a middle linebacker intensity. He was the heart and soul of the 1977 and 1978 World Champions. He was the Yankees captain, the first since Lou Gehrig in 1939. Joe DiMaggio, Yogi Berra and Mickey Mantle were never Yankee captains. Thurman Munson was. He had that all important hat trick of talent, leadership and respect. Munson, who on the surface was a mustachioed, snarly curmudgeon, was loved by everyone in his locker room except for maybe Reggie Jackson. Ironically, that made Thurman even more lovable, probably to non-Yankees fans, too.

He played eleven seasons in pinstripes, was a seven time All-Star, three-time Gold Glove winner, the American League Rookie of the Year in 1970, and the AL Most Valuable Player in 1976. However, in death, Munson was slighted by baseball and baseball journalists. A lifetime .292 hitter and with all the credentials above, he’s not in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. His two main rivals during his era and lifetime— Carlton Fisk and Johnny Bench, are. Munson’s career batting average was over 25 points higher than either Fisk or Bench. Granted his resume was shortened by death but pretty strong for eleven seasons. Had he lived, and continued the same productivity, he easily would have been a first ballot inductee. Instead, for decades and still today, there is a move afoot by Munson fans to have him enshrined by the Era Committee in the Hall. It has not gained any momentum.

His #15 will never be worn by a Yankee again, except by dozens of Yankees fans and fantasy campers. He hated the Red Sox with all the fire and passion he could muster, and he played like it. Yankee fans revered him.

To me, Thurman Munson was more than a legend when he died in 1979 at the age of thirty-two, loving what he was doing at the time even more than baseball: piloting his own airplane. It was that Cessna Citation that allowed him to fly home to Canton, Ohio, numerous times during the long baseball season to see his wife Diana and their kids. The crash happened during an off day for the Yankees while Munson was doing a practice run of touch and go landings at the Akron-Canton Airport. His two passengers walked off the aircraft but Munson, with a broken neck, died of asphyxiation from the flames.

Thurman was the first baseball player I ever personally knew. More importantly, he was the first baseball player that ever knew me. If you were a kid growing up during the 50s and 60s, you know what a big deal that was. We idolized ballplayers. We wanted to be them. We got to see them play on black and white televisions, had their baseball trading cards and engrossed ourselves in daily newspaper box scores. Weekly we waited for the Sporting News or Baseball Digest to hit our mailbox learning as much about our heroes stats as our young teenage minds could comprehend. If we were lucky enough to go to a ballgame we saw them from a distance and maybe, just maybe, during batting practice we could get close enough to the field to yell something in their direction and get a nod of approval. Oh my — ecstasy, when that happened.

We eventually grew up not being professional baseball players and after a while that was okay. Idolatry gave way to reality, and we lived our lives the way as our lives were meant to be lived. Ultimately, a diamond meant a commitment and a not a place to spend nine innings.

I met Thurman for the first time in 1976 when the Yankees held their spring training in Fort Lauderdale, FL when I was a twenty-four year old director of public relations at nearby Hollywood Greyhound Track, a pari-mutuel racing facility. With mainly daytime exhibition games, Thurman loved to bet the dogs in the evenings. The Yankees PR department would phone me ahead of time to tell me he and Diana would be coming to the track for dinner and wanted me to have a table reserved for them in our popular restaurant. They would come to the track by themselves but Munson always wanted a table for four so he could spread out the racing program and tout sheets while they would eat and wager. After a while Thurman would phone me directly to let me know he was coming to the track and I would spend part of the evening visiting with them. Well, more with Diana. Her husband had his head mired in the racing form like an underperforming college student cramming for a math final early the next morning. One night, somehow, I was able to distract him enough to come down with me to the winner’s circle for a picture with the race winner. It remains one of my baseball treasures.

Gruff on the outside, Munson was really a kind, gentle man unless you were Carlton Fisk or a reporter. Easily recognizable, he was a bit shy, but at the racetrack he wouldn’t turn his back on any fan acknowledgment, instead giving a nod or saying hello. Former Yankee president Gabe Paul once said, “Thurman Munson is a nice guy who doesn’t want anyone to know it.” My son Jason, born a year after Thurman’s death, still has the mind’s eye picture of what we all remember— “A bushy mustache, a wad in his cheek and pure 1970s baseball grit.”

Our friendship would rekindle every spring when the Yankees were in training camp. He would freely call, and the Hollywood switchboard operator was told to always find me. I wasn’t going to miss a Thurman Munson phone call, especially since, and unbeknownst to me at the time, he was transitioning me from a lifelong PIttsburgh Pirates fan and Yankees hater to a staunch Yankees lover. I’m still not sure how that happened, but it did, and it stuck.

The summer of 1978 was my greatest Thurman Munson memory. It was the weekend after Labor Day. Six weeks earlier the Yankees trailed the Red Sox by fourteen games in the standings. George Steinbrenner fired Billy Martin for the first of five times and brought in Bob Lemon to steady the ship. It was like replacing Donald Trump with Mr. Rogers. When the Yankees hit Fenway Park in September they were on fire and only trailed by four games.

The weekend became known in Yankees’ annals as the ‘Boston Massacre’ with the good guys sweeping the four-game series by a combined score of 42-9, leaving the Back Bay in a tie for first place.

I went to the Saturday afternoon game of the ‘78 series with Greg Farley, the racing writer for the Boston Herald-American, who to this day is still a close friend. Things were going so well for the Yankees that long-forgotten Jim Beattie, with a record of 3-7, pitched into the ninth with the Yankees winning a 13-2 laugher to close the gap in the standings to only one game.

That night Greg and I went to the greyhound races and dinner at nearby Wonderland Park. As we walked into the clubhouse restaurant and the host was leading us to our table we heard a loud shout: “Roy, what are you doing here?” It was Munson at a table with Mickey Rivers, Lou Piniella, Graig Nettles and Ron Guidry, who won twenty-five games and the American League Cy Young award that season. There may have been one or two others in the group, but I was so startled I didn’t take attendance.

Ironically, a dozen years later in 1990, I became the general manager of Wonderland.

Back to ‘78 and Thurman asking me sit down and join them. I felt like Dan Quayle at dinner with Churchill, FDR and General MacArthur. I’m certain the other Yankees had no idea who or why this guy with a bad Afro, who looked like Mr. Kotter, was sitting with them. I laughed when I was supposed to; I rooted for their bets to win and sat in awe the rest of the time. I have no idea what happened to Greg Farley that night but hope he enjoyed dinner as much as I did.

The weekend was a prelude of what was to come for the Yankees. Finishing in a regular season tie with the Red Sox it paved the way for Bucky Dent’s career hit in a one game winner-take-all playoff; then the Yankees beat KC in the ALCS and the Dodgers in six in the World Series for back-to-back championships.

Martin had been ‘unfired’ by Steinbrenner and was back in the manager’s office in 1979. Munson, now into his early thirties, was beginning to focus on post-career business opportunities and was interested in me helping him put together an investment group to purchase a greyhound racing track in Vermont that was on the market. He learned the hard way that the only way to make money in the racing game was to own the track. He wanted me to manage it for him. He promised he’d be more patient with me than Mr. Steinbrenner was with his managers. Comforting. But we never got the chance.

August 2, 1979 happened. I was working in Connecticut that summer. It was a month before ESPN went on air for the first time and a couple of decades before what became social media, but still the news of the airplane accident traveled quickly over network and radio airwaves. Four days later, courtesy of colleague Aaron Silver, we flew privately to Thurman’s funeral in Canton, Ohio and ironically landed at the same airfield as his accident. We left graveside and flew to the Bronx to watch the Yankees and Orioles in a game the Yankees, still shellshocked and just returning from the funeral, didn’t want to play. However 36,000 were on hand for what resembled a wake, still weeping as a tribute to our fallen leader. Bobby Murcer, Munson’s best friend on the Yankees, gave us chills walking-off the Orioles 5-4 in the bottom of the ninth.

No doubt, the Captain left way too early but he was chasing his passion of flight and family. He died as he lived—a nice guy who didn’t want anyone to know it.

I’m proud that Medjet is sponsoring Sunday Morning Coffee. I spent 20 wonderful years with Medjet in Birmingham, Alabama, and can tell you unequivocally they are the standard-bearer for medical assistance membership programs. A talented staff, who cares about its members, is at the forefront of the company’s success. Whether you are traveling for business or pleasure, domestic or international, a Medjet membership should be an important part of your travel portfolio before you leave home. Check out the Medjet website at medjet.com or just tap on the Medjet logo and you’ll be able to get a look at Medjet’s services, rules and regulations, pricing, and an overview of the organization. And remember, any opinions expressed in Sunday Morning Coffee content or comments belong to the author and not the sponsor. Safe travels with your Medjet membership! — Roy Berger

Fantastic blog. This is one of my favorites you have written. I remember this day so well. I went on a job interview and broke down during the meeting with the man who became my boss. He asked was I OK. I apologized stating Thurman Munson was just killed in a plane crash. With that being said I pulled myself together and the job was mine. I have to say you have met some outstanding people throughout your life and created special memories. Excellent read about a man who left us way too early. So enjoyed this!!!

Two things I’ve noticed about Thurman watching old footage of him:

1) He called all the pitches — every single one. Martin and Lemon trusted him enough to do that. (Now of course, the pitches come from the dugout, or (gasp) the front office.)

2) When he was at the plate, you could swear he was whacking weeds, his approach was so fluid. He’d take a couple practice swings — half-hearted one-handed semicircles — and then in one motion whack the ball, usually spraying a line-drive anywhere around the field. He batted .373 in the 1976 World Series as the rest of his teammates were swept by the Reds, and was seriously considered to be the MVP *on a losing team*.

3) Dave Anderson (the Pulitzer-Prize–winning NYTimes sports columnist [back when the Times had a sports section]) had a great column about Munson’s funeral — specifically about one visitor. He was Thurman’s dad, who unceremoniously walked out on his mom, just stricken with a stroke, several years prior. Before that, he was hardly home. Diane swears (and Thurman agreed) that the one good thing from that experience was her husband’s absolute conviction to not be like him, and his insistence on being able to fly to Canton during off-days to see her and their kids. Anderson, in dry prose, described in clear-cut detail how his dad clearly never changed from the slimy shyster we imagined him to be:

https://www.nytimes.com/1979/08/07/archives/the-man-in-the-white-shirt-sports-of-the-times.html?unlocked_article_code=1.cU8.SRv7.htgjyH8jfmVx&smid=url-share

4) Despite appearances — and a terribly rocky start stemming from Jackson’s odd Sport Magazine interview — Reggie Jackson and Munson grew closer as their time together progressed. There’s a reason Diane requested that four telegrams, out of the hundreds sent to her, be read at the eulogy: those from Lou Piniella’s wife, Muhammed Ali, Lou Gehrig’s widow, and … Reggie Jackson.